Irving Penn (1917 – 2009) was an American photographer known for his fashion photography, portraits and still lives. Worlds in a Small Room, was a collection of photographs taken by Penn spanning a period of over 20 years which were taken whilst he was working on fashion shoots for Vogue. The photographs are portraits shot in studio conditions and started with a trip to Cusco, Peru, in 1948 where he hired a daylight studio to photograph with Northern light (Penn, 1974). Later on he had a custom studio tent built which he used on field trips between 1967 and 71. The book Worlds in a small room was published in 1974; all the images were taken using a Rolleiflex camera.

In addition to the photographs taken in Cusco, the photographs published in Worlds in a Small Room can be split into three separate groups. Between 1950 – 51, Penn photographed artisans and blue collar workers in Paris, London and New York, where he was covering fashion collections for Vogue, in a series titled Small Trades. Shot in a studio, the subjects were instructed to wear their work clothes.

Between 1964 – 67 Penn used improvised studios whilst working in Crete, Extramadura (Spain) and San Francisco. Penn continued to use the same approach as he had done with his earlier work, shooting using natural light against a neutral background.

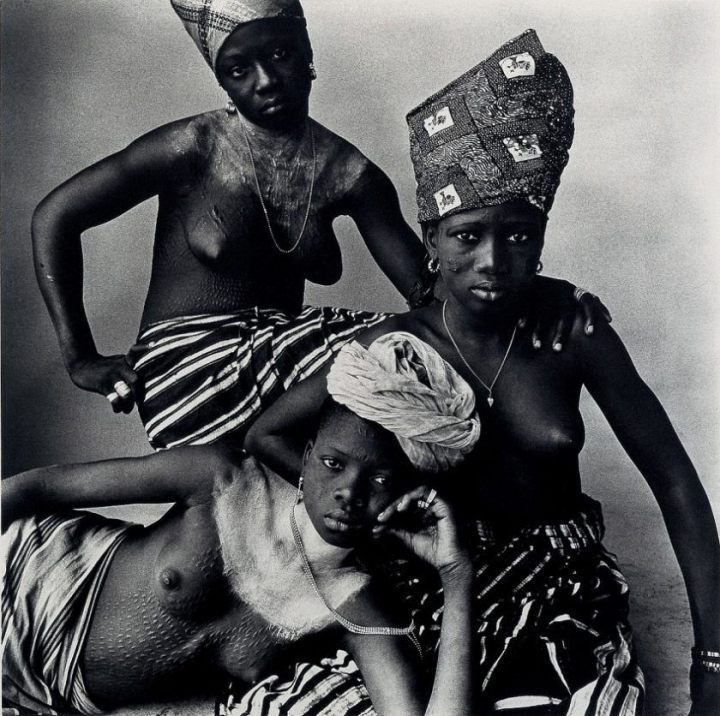

The final evolution of Penn’s approach were the images produced between 1967 – 71 using a portable studio tent that Penn had had made. During this period he photographed inhabitants of Dahomey (Benin), Nepal, Cameroon, New Guinea and Morocco. Like all the images, these works were meticulously arranged and posed with Penn often manhandling the subjects due to the lack of a common language.

I have been unable to find any meaningful reviews of the book from a photographic perspective, however, it was reviewed in 1977 in the academic journal Studies in Visual Communication. The review, written by Jay Ruby who was a professor in the Anthropology department at Temple University until his retirement in 2003. Ruby was not a fan of the book and in the summary of the review states:

If Penn were less of a photographic artist, the moral dilemma would not be so apparent. I am moved by the beauty of an image which has been constructed because a photographer was able to find people who were sufficiently passive to allow themselves to become aesthetic objects. Science and particularly the social sciences have been soundly criticized for dehumanizing people and exploiting them as subjects and informants (both terms suggest a submissive role) in the name of science. It is revealing to see that photographic artists can be open to the same criticism. A photographic aesthetic based on the objectification of human beings is as ethically problematic as scientific methods which employ people as informants. If we question one it seems reasonable to subject the other to similar scrutiny.

Jay Ruby, Studies in Visual Sommunication, Vol. 4 Iss. 1

It is difficult to comment knowledgably on Penn’s work without seeing it first hand, however, from the images I have seen online it strikes me that the whilst Penn’s aims were well intentioned, trying to record a world that was soon to disappear, the work was compromised by his technique of photographing his subjects in a studio environment and also by the changes to the world in the twenty year period it took to produce the work. Taking portraits of tradesmen in Paris, London and New York or Hell’s Angels on Los Angeles does not appear exploitative, however, Penn’s ‘ethnographic’ images, photographing people whose understanding of Western society would be, at best, limited or more likely non-existent does appear to exploit them.

In notes held by the Art Institute of Chicago, Penn wrote about his idea to photograph people outside the mainstram of society:

In my early years as a photographer, confined to an enclosed windowless area working in a New York office building, even here were electric light banks to simulate the light of the sky…. In this confinement I would often daydream of being mysteriously deposed in my ideal studio among the disappearing aborigines of course in remote parts of the earth. In my phantasies [sic] these remarkable strangers would come to me and place themselves in front of my camera and in the clear north sky light I would make records of their physical presence, pictures that would survive us both and at least to the extent something of their already disappearing cultures would be forever preserved.

I can say that even at that time pictures trying to show people in their “natural circumstances” were for me generally disappointing. Certainly I know that to accomplish such a result was beyond my strength and capabilities. I preferred in this fantasy of mine, the limited objective of dealing only with the person himself, in his own clothes and adornments away from the accidentals of his daily life. From him alone I would distill the image I wanted and the cold light of the day would put it into the film.

Irving Penn

I think the above quotation from Penn is very enlightening; Penn talks about his fantasy of creating images where the indivivudals are removed from their daily life and are photographed in their clothes and adornments. He also dismisses the idea of showing them these people in their ‘natutal circumstances’ as feels he it is beyond his abilities to photograph his imaginary subjects in their natural environment. In essence Penn is describing shooting a fashion image containing the model, clothes and accessories in the studio environment he is used to. The image Three Dahomey Girls, One Reclining, shown below makes this point and by shooting the women against a plain background, and removing them from the world they inhabit, Penn created an ethnic fashion image using models that were more exotic than the American or European models he would have used when shooting from Vogue.

Like Jay Ruby I find that the images are well composed, the lighting and simple backdrop combining to produce engaging images. However, the images of indigineous peoples that Penn had to manhandle into the poses he wanted leave me feeling uneasy as to me they have an undertone of colonialism and Western superiority.

Sources

Ruby, J. (1977). Penn: Worlds in a Small Room. 4 (1), 62-63. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol4/iss1/6 [Accessed: 26/02/20]

Penn, I., n.d. Ethnographic Studies | The Art Institute Of Chicago. [online] Archive.artic.edu. Available at: <https://archive.artic.edu/irvingpennarchives/ethnographic/> [Accessed 22 March 2020].

One thought on “Irving Penn – Worlds in a Small Room”