Do some research into historic portrait photography. Select one portrait to really study in depth. Write a maximum of 500 words about this portrait, but don’t merely ‘describe’ what you see. The idea behind this exercise is to encourage you to be more reflective in your written work (see Introduction), which means trying to elaborate upon the feelings and emotions evoked whilst viewing an image, perhaps developing a more imaginative investment for the image.

The origins of modern photography can be traced back to the beginning of 1839 when Francois Arago, a member of the Chamber of Deputies, made a statement to the French Academy of Science describing the process for producing a Daguerreotype, the method of creating a photographic image developed by Louis Daguerre (Marien, 2014, 14).

In the United Kingdom, William Fox Talbot who had been working on the development of his Calotype process since 1833, wrote to Arago to claim prior invention and presented a paper he had written to the Royal Society on the 31st January 1839, three and half weeks after Arago’s statement (Marien, 2014, 16).

Although Daguerre’s process created images with greater detail and clarity, they were not reproduceable and it would be Fox Talbot’s negative-positive process that would be developed into the negative film which lead to the growth of photography in the 20th century.

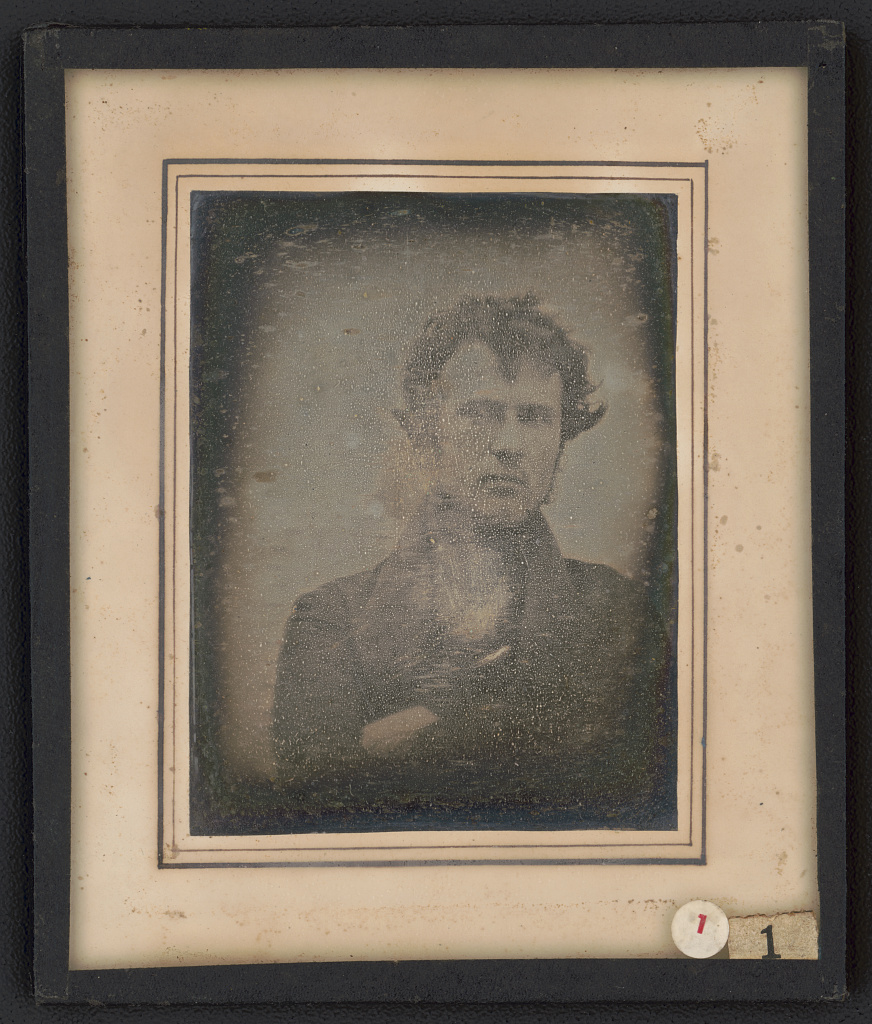

Later in 1839, Robert Cornelius, an amateur photographer from Philadelphia, produced what is thought to be the world’s first photographic portrait, or more accurately self-portrait. The 9 x 7 cm Daguerreotype has an inscription on the back which states ‘The first light picture ever taken. 1839’ and is part of the collection of Daguerreotypes held by the Library of Congress in Washington DC.

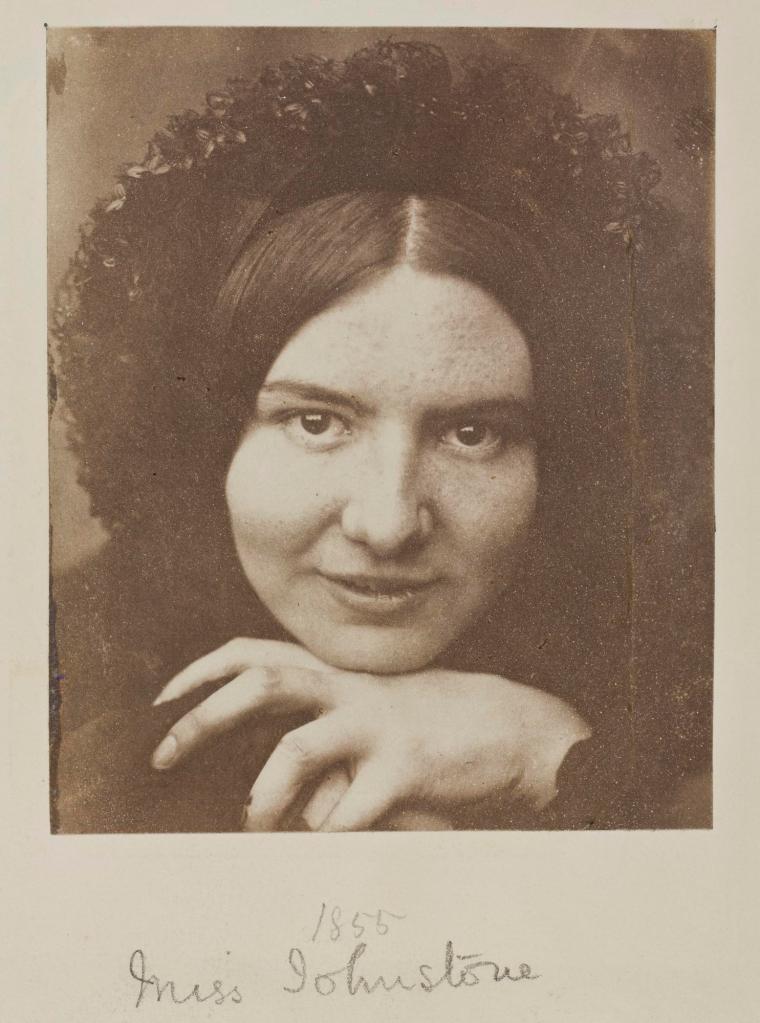

Despite its historical significance this is not the image that I want to study. The image that I want to examine in detail is a calotype, the negative-positive process patented in 1841 by William Fox Talbot, taken by Dr John Adamson in Scotland in the 1850s. Adamson was a doctor, physicist, and museum curator as well as a photographer and in 1841 he was responsible for producing the first calotype portrait in Scotland (En.wikipedia.org, 2019).

The image, a calotype albumen print from a wet collodion negative, was taken by Dr John Adamson in the 1850s, possibly 1855, and is one of two images of Miss Johnstone held by the National Museum of Scotland. Adamson was the elder brother of Robert Adamson, a pioneering Victorian photographer who worked David Octavius Hill to produce around 2,500 calotypes between 1843 and Adamson’s death in January 1848.

What drew me to this picture was its unusualness, the composition could be contemporary but it was taken over 150 years ago. Miss Johnstone’s face is central in the frame, her chin resting on her crossed hands and her eyes looking directly at the camera with clearly visible catchlights. She is wearing some form of headdress, although this is difficult to distinguish against her dark hair, and there is a faint smile on her lips.

The composition of the image contrasts markedly with most of the other portraits I have seen from the mid-1800s. Below is an image produced by Hill and Adamson between 1843 and 1848 of Isabella Morrison Bell (née Adamson), Robert and John Adamson’s sister.

The composition is fairly typical, a half-length portrait with the subject seated and looking out of the frame. The contrast between the two images is very marked; the image of Miss Johnstone is intimate, almost sensual. There are several elements that signify this intimacy; the decision to photograph just the sitter’s face which enables the viewer to see clearly her features, the fact that Miss Johnstone has a relaxed smile and the way that her eyes, which are clearly visible, are looking directly at the camera. In addition to her smile and expression, Miss Johnstone’s pose, with her chin resting on her crossed hands contributes to the feeling of intimacy. These elements suggest that atmosphere when the photograph was taken was relaxed and informal and that the sitter and photographer were comfortable in each other’s company. In contrast the portrait of Isabella Bell has a much more formal air about it even though one of the photographers was her brother.

The image displays none of the formality we associate with the Victorian period and having looked at the photograph I am intrigued about the relationship between Adamson and Johnstone. From the title and the photograph it is clear that Miss Johnstone was neither married or engaged, and I am left wondering about the dynamic between the two individuals responsible for creating this image. What was it about Adamson that created a relaxed environment which enabled such an intimate image to be photographed? And what about the situation did Miss Johnstone find so agreeable for her to pose so candidly for the camera? We will never know the answers to these questions but what we can admire is a portrait that reveals as much about the photographer as his subject and much more than most of the portraits from this period.

Sources

Marien, M. (2014). Photography. 4th ed. London: Laurence King Publishing, p.14.

Marien, M. (2014). Photography. 4th ed. London: Laurence King Publishing, p.16.

Cornelius, R. (1839). Robert Cornelius, self-portrait. [Daguerreotype] Washington: Library of Congress.

Adamson, J. (1855). Miss Johnstone. [Caloytpe] Edinburgh: National Museum of Scotland.

Hill, D. and Adamson, R. (1843-1848). Isabella Morrison Bell (née Adamson). [Calotype] London: National Portrait Gallery.

En.wikipedia.org. (2019). John Adamson (physician). [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Adamson_(physician) [Accessed 27 Dec. 2019].

Photography – A Victorian Sensation – Portraits. (2015). Edinburgh: Museum of Scotland/ University of Edinburgh.